Black Art and Anti-Colonial Resistance: Reflections about Paris Noir

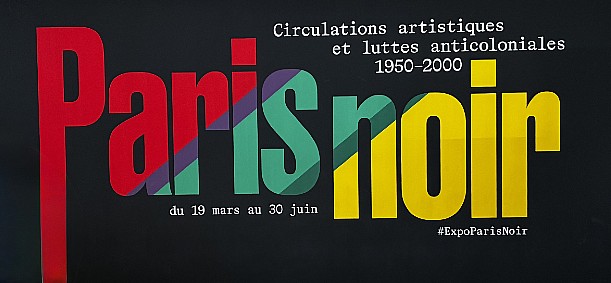

Writing from Paris, I recently visited (May 2025) the exhibition “Paris Noir – Artistic Circulations and Anti-Colonial Resistance, 1950 – 2000”1 at the Pompidou Centre. This extensive exhibition tracks the evolution and growing influence of black artists in Paris from the 1950s to the present, and walking through it reminded me of how international art movements have drawn generations of artists into broader cultural conversations. The exhibition brings together works by 150 artists from Africa, the Americas, the Caribbean, and Europe, many of whom are being seen in France for the first time.

The exhibition draws Black artists into the mainstream narrative of Western art. Originally, the modernist vanguard artists like Picasso heavily relied on African, Eastern and Middle Eastern art for their inspiration. This exhibition reveals how the black artists reciprocated by using Western visual language and styles to convey their anti-colonial message.

What struck me as an Australian visitor to this exhibition was that I had no idea this international movement existed for black artists. Remember, this exhibition focuses on artistic developments across Paris, Belgium, Africa and the United States, not Australia, because our First Nations artists weren’t in Paris during the time frame.

Australia has a much longer history of artists pushing back against colonialism than many people are aware of. You could say it began with Tommy McRae (c.1835–1901)3 and William Barak (1823–1903)2, both of whom witnessed first contact and created a compelling visual record of Europeans occupying their land. Barak, while serving as a leader at Coranderrk Reserve outside Melbourne, advocated for First Nations rights. Although these works don't explicitly voice protest, it would be impossible for them not to have been distressed by what they witnessed and experienced.

Early exhibitions of First Nations art, including "Australian Aboriginal Art" (1929) and "Art of Arnhem Land" (1929), operated within ethnographic rather than artistic frameworks. More explicit political expression emerged with the Yirrkala Bark Petitions (1963)4, which combined traditional bark painting with typed text to protest mining on traditional lands. This was the first formal Indigenous protest against land appropriation using art as political expression, with the bark paintings presented to the Federal Government to demonstrate the Yolngu people's connection to their country.

Later, works like the Ngurrara Canvas (1996)4 continued this tradition, created for native title cases. However, both the Yirrkala Bark Petitions and the Ngurrara Canvas functioned as legal evidence rather than pure protest art, as they served legal and political purposes simultaneously.

Contemporary urban Indigenous artists, including Lin Onus, Vincent Namatjira, Vernon Ah Kee and Adam Hill, work within Western art traditions while maintaining strong anti-colonial perspectives. Before encountering “Paris Noir”, I had assumed these artists’ anti-colonial stance was purely local. The Paris Noir exhibition instead revealed a long history of anti-colonial art from Paris, Africa and the United States—a global conversation Australian artists were part of, whether consciously or not.

As an aside, the first mention I could find of Australian First Nations artists in Paris was in 1983 with the exhibition “D’un autre continent: l’Australie la rêve et le réel,” at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. The exhibition featured a ground painting by the Warlpiri men from Lajamanu. This event marked one of the earliest high-profile presences of Indigenous Australian artists in Paris, although these artists weren’t residents. It is likely an area where further research could be done.

Current Australian curatorial priorities have shifted noticeably since the 1970s, and colonial-era paintings by once celebrated artists like William Charles Piguenit (1836–1914), John Glover (1767–1849), Nicholas Chevalier (1828–1902) and Eugene Von Gerrard (1811–1901), while still drawing big bids at auction, now seldom appear outside the permanent collections in curated exhibitions.

What emerges from this comparison is interesting: First Nations Australian artists have, with some success, used art not merely as a protest, but as a legal instrument. The Yirrkala Bark Petitions and Ngurrara Canvas were likely the first artworks used in anti-colonial land rights cases, therefore, it can be argued that they belong to the international movement that “Paris Noir” documents.

The exhibition's value to Australians lies in highlighting these global connections, revealing that artistic resistance to colonialism was an international conversation, even when individual artists appeared to work in isolation.

Footnotes

- The exhibition “Paris Noir: Artistic Circulations and Anti-Colonial Resistance, 1950–2000” at the Pompidou Centre offers a profound exploration of black artistic legacies in Paris. Spanning painting, sculpture, photography and multimedia installations, it showcases over 350 works by more than 150 artists from Africa, the Americas and the Caribbean. This exhibition challenges traditional narratives of modern art by highlighting the contributions of black artists, who are often marginalised in mainstream art history. ?

- William Barak (1823–1903) was a Wurundjeri ngurungaeta (head man) from the area now called Melbourne. He lived through the dramatic changes of European colonisation, witnessing as a child the founding of Melbourne. Barak created important drawings documenting both Wurundjeri ceremonies and colonial encounters. He was also a significant political leader who advocated for his people at Coranderrk Reserve and created art that recorded cultural knowledge and depicted the impact of colonisation. ?

- Tommy McRae (c.1835–1901) was a Kwat Kwat man from the Murray River region of Victoria. His pen and ink drawings from the late 19th century documented both traditional Aboriginal life and interactions with European settlers, including scenes of first contact, settlers’ activities and Aboriginal ceremonies. His work provides a rare Indigenous perspective on colonisation from this period. ?

- See https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/yirrkala-bark-petitions for more information.

-

Significant First Nations exhibitions:

- "Glorious Days" (Museum of Victoria, 1913)

- "Australian Aboriginal Art" (National Museum, Melbourne, 1929)

- “The Art of Arnhem Land” (Western Australian Museum, 1957)

- “Australian Aboriginal Art” (Art Gallery of New South Wales touring exhibition, 1960–61)

- “The Art of Aboriginal Australia” (North American tour, 1974–76)

- “Aboriginal Art at the Top” (Darwin, 1982)

- “Expo ’88: The Art of Central Australia” (Expo Authority Pavilion, Brisbane, 1988)

-

List of important senior artists

Also see: “The Art of Aboriginal Australia” (1974–76 North American tour) and “Aboriginal Art: The Continuing Tradition” at the National Gallery of Australia (1989). Curly Bardkadubbu entered the first National Aboriginal Art Award, established by the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory in 1984. - You can also refer to our sister website https://artbiogs.com which includes the online title NATSIVAD (Natioanl Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies database)